There is a superb article in the FT that’s worth a subscription to the paper alone! I’m not going to reproduce the whole article (mindful of the rules of Copyright etc.,) but I wanted to share the meat of the piece for those trying to find a home to move to. If you are finding the process frustrating, if you can’t find suitable properties or if most seem to be sold before you have even been even able to book a viewing you’re not alone and George Hammond can explain why.

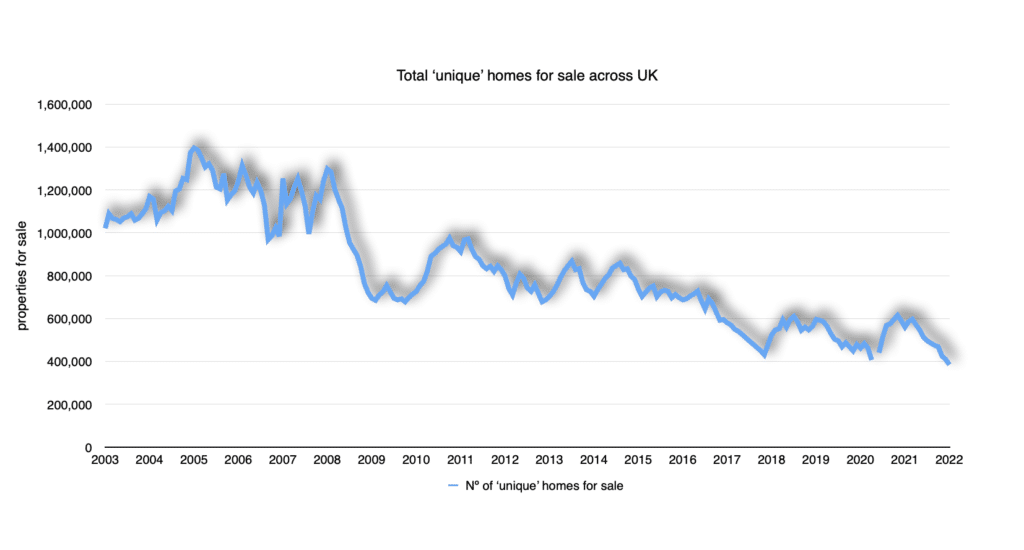

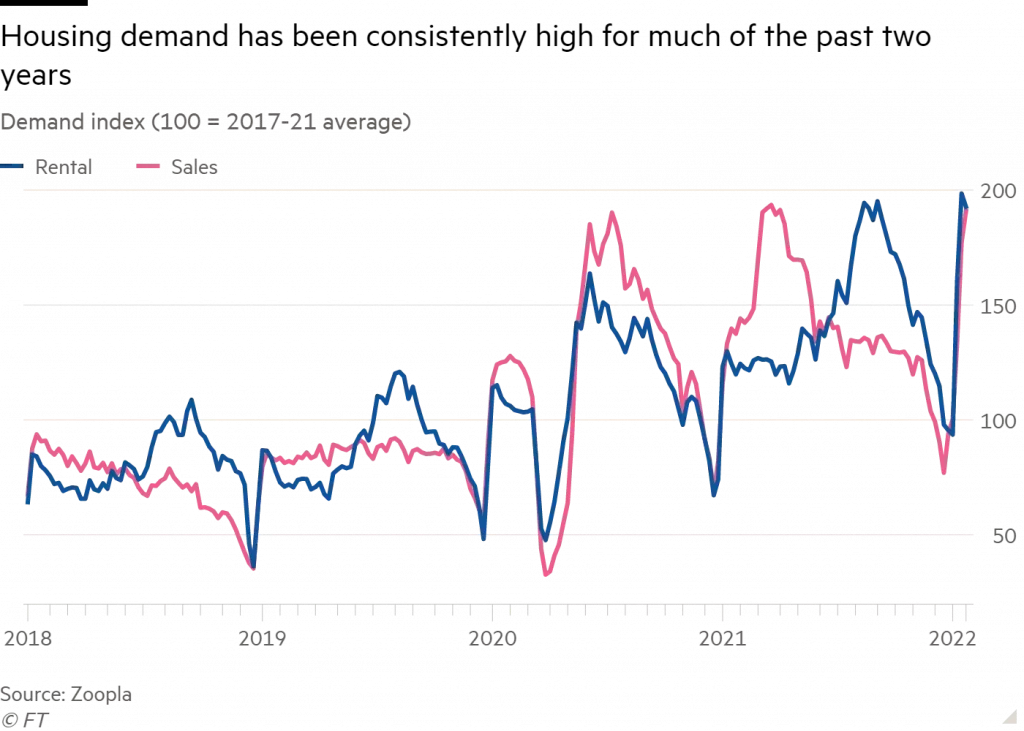

“Demand is at historic highs — the number of prospective buyers contacting estate agents about properties is close to double the recent average, according to property portal Zoopla — and supply has dwindled. At the start of this year there were 350,980 properties for sale in the UK, according to consultancy TwentyCi, 36 per cent fewer than at the start of 2020, and the lowest amount since the company began collecting data in 2008. At the same time, the number of homes available to rent is also at rock bottom, with prospective tenants reporting they have had to jostle their way on to shortlists just to view a property. “In my living memory, we’ve never been in this situation before,” says Colin Bradshaw, managing director at TwentyCi. “The lack of supply has broken the sale and lettings markets.” So how did we get here? Richard Donnell, executive director at Zoopla, says demand has consistently run above supply for the past two years.

“Boris Johnson’s election as prime minister in December 2019 made the outcome of protracted Brexit negotiations more certain and banished the prospective tax implications of a Corbyn-led government. That gave some buyers confidence to enter the market. While the pandemic halted the buying and selling of homes in England for seven weeks in spring 2020, when the market reopened in May, buyers came out in force. Demand was only boosted in July of that year, when chancellor Rishi Sunak introduced a stamp duty holiday on the first £500,000 of all property purchases, providing a tax break of up to £15,000 in the process.

“In the intervening 18 months, the UK’s average house price has risen by nearly 16 per cent, according to mortgage provider Nationwide. Despite the tax holiday’s withdrawal in September last year, demand is as high as it was when it was introduced. “It’s bananas,” says Donnell. In recent years around 1.2mn homes have traded annually, but Donnell estimates that in the past year about 1.5mn were exchanged.

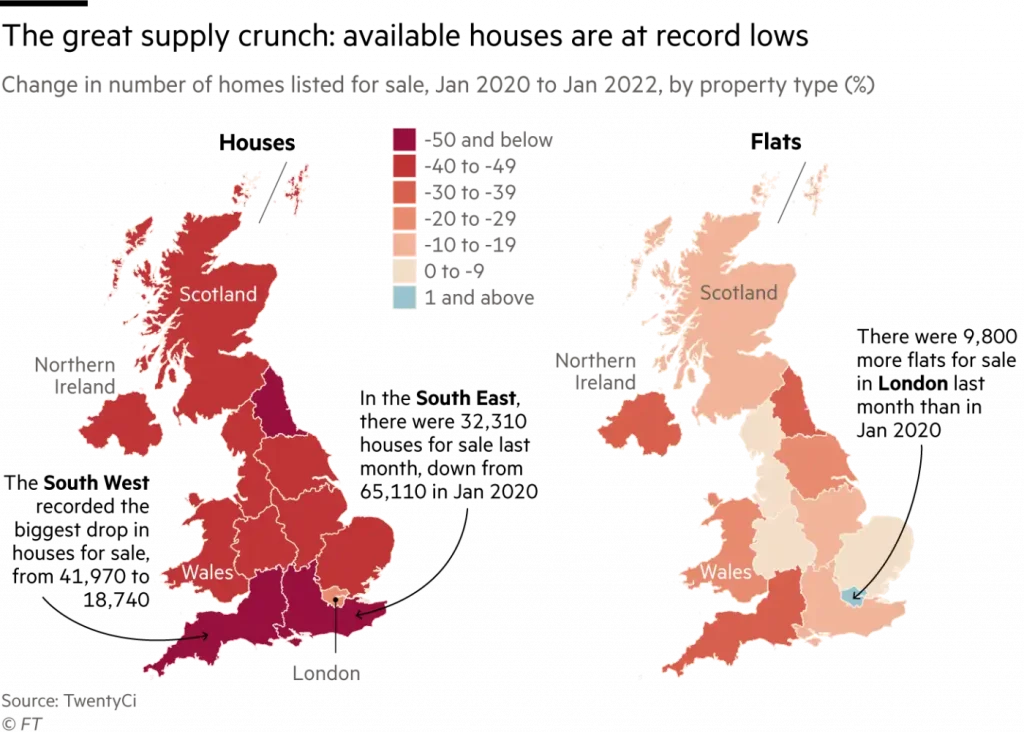

“The pandemic has also shifted what buyers are looking for, making the supply crunch particularly acute in some pockets of the market. Larger homes with gardens and spare bedrooms that can double as home offices are top of most buyers’ wish lists; flats are bottom. This is especially a problem in London, where there is a growing mismatch between what is for sale and what buyers want. The number of homes listed for sale in the capital has actually gone up in the past two years, from 71,850 in January 2020 to 75,470 last month, according to TwentyCi. During that time, the number of detached and semi-detached houses on the market has dropped by about a third, but the number of flats has risen by about 20 per cent. Today, four out of five homes for sale in London are flats.

“In a marketplace where many buyers are also sellers, why is it that the stock is depleting so fast? Around a third of homes are bought by first-time buyers, who have nothing to sell, and a further 10 per cent are sold to buy-to-let investors, explains Donnell.

“In recent years between 200,000 and 240,000 new homes have been added to the mix each year, and tens of thousands more become available when their owners die. But the delivery of new housing in England fell back last year for the first time in almost a decade as lockdowns and supply chain issues slowed construction work. The country’s biggest developers have warned that ramping up building will be made harder by housing secretary Michael Gove’s tough new stance on the sector. Gove has told developers they will have to find billions of pounds to fix flats caught up in the cladding crisis, which has ballooned in the four and half years since a fatal fire at Grenfell Tower in west London exposed deep and widespread building safety issues. The effect of those homes — which could number more than 800,000 across the UK — on the supply crunch is complicated. Many are effectively unsaleable: until they have been signed off by a fire safety expert, lenders will not issue mortgages against them. While this is stopping these homes coming to market, it also prevents their owners from trading up from a flat to a house.

“When properties do appear in estate agents’ windows, they are rarely there long, piling more pressure on to buyers who have a paucity of options. At the outset of 2020, two-thirds of homes for sale had been listed for six months or more, according to TwentyCi. Last month, fewer than one in five had been on the market so long. Roughly half of homes now sell in less than eight weeks, a quarter are gone in under four. But again, it depends on what and where you’re selling: in the last three months of 2021, it took on average 23 days for houses outside of London to be sold subject to contract, according to Zoopla. Flats in the capital took 64 days on average to shift.

“The result is that power currently resides with sellers, enabling them to push up prices in high-demand areas. Most sellers will also be buying a property, but many are choosing to find their future home before jettisoning their present one, says Donnell. That is making supply appear even tighter than it might otherwise be, and the crunch would be partially alleviated if sellers listed their homes while they themselves were hunting somewhere new. But few are doing so, partly out of fear that if they sell up they might spend months in rental limbo and miss out on house price growth they would otherwise have benefited from.